To uncover a tale of development spanning two continents, James Churchill shoots the breeze with Peter Hajba and Scott Miller about bullet time, hitscanning and 3D animating via camcorder footage.

“They were all dead. The final gunshot was an exclamation mark to everything that had led to this point. I released my finger from the trigger. And then it was over.” The first words spoken by Max Payne as the camera tracks up an industrial skyscraper in a New York blizzard brilliantly set the stage for one of the most atmospheric and celebrated shooters ever made. A game that popularised bullet time within the action genre, and contained inspirations spanning film noir, Norse mythology, graphic novels and Hong Kong action movies whilst interweaving the tale of Max’s revenge for the murder of his family. In 2001, action games didn’t come more badass than this.

But to make any sense of the trail leading up to the high octane blockbuster hit, we need to go back to 1996, when Max Payne developers Remedy Entertainment had just released their first game for MS-DOS: Death Rally; a top-down vehicular combat title that received mostly positive reviews. But for future efforts the company wished to expand. “Samuli Syvähuoko, the CEO of Remedy, called me and asked if I'd like to join them to work on a new game.” says Peter Hajba, responsible for multiple roles including animation, particle effects and texture art. “I was studying animation in a college in Dublin and was originally going to study for three years, but I accepted the offer and moved to Espoo.” And like any young developer, the Finnish studio had humble beginnings. “Remedy was established in the basement of the house of one of our founders.” Peter explains. “From there we proceeded to rent a real office space. The atmosphere gradually slid from garage band to professional.”

For their next venture Remedy wished to continue their working partnership with American-based publisher Apogee Software, which had transitioned to releasing all future games under the name 3D Realms. Apogee founder Scott Miller recalls Remedy’s ambitious plans. “The creative minds at Remedy put together three project ideas that they wanted to present to me, to see if any of them looked promising as a full-blown game. One of them was a 3D racing game, one was a space battle RTS game that would have been a little like Homeworld had it ever come out, and the final idea was a top-down isometric shooter in the style of Loaded, which they were calling Dark Justice. Surprisingly to me, they had it in mind to make all three games at the same time!”

However, Scott’s input as a veteran developer and publisher encouraged Remedy to solely develop the Dark Justice project. “I still remember the meeting I had with a group of the top Remedy execs who came to Dallas from Finland,” he recalls, “I was selling them on the big-picture idea of building a strong character-driven transmedia franchise with a compelling story, unique character traits, and naming the game based on the lead character like we had done with Duke Nukem. At that first meeting I even said, ‘Guys, if we're successful, there will be a film based on this character and his story.’ And sure enough, that ended up happening.”

But to achieve the success Scott outlined, a catchy marketable name was needed. “I finally came up with Max,” Scott explains. “We had the last name Heat, and although we all knew it wasn't perfect, we went and got a trademark on Max Heat mostly as a back-up plan.” Scott estimates this process cost $15,000, but 3D Realms and Remedy still sought perfection. “It finally arrived in an email from Remedy a month or so later. They had asked their internal team to submit the best last names they could think of, and I was looking over this list of about thirty to forty names, and BOOM, there was Payne. It was a ‘holy shit!’ moment because I immediately knew it was perfect.”

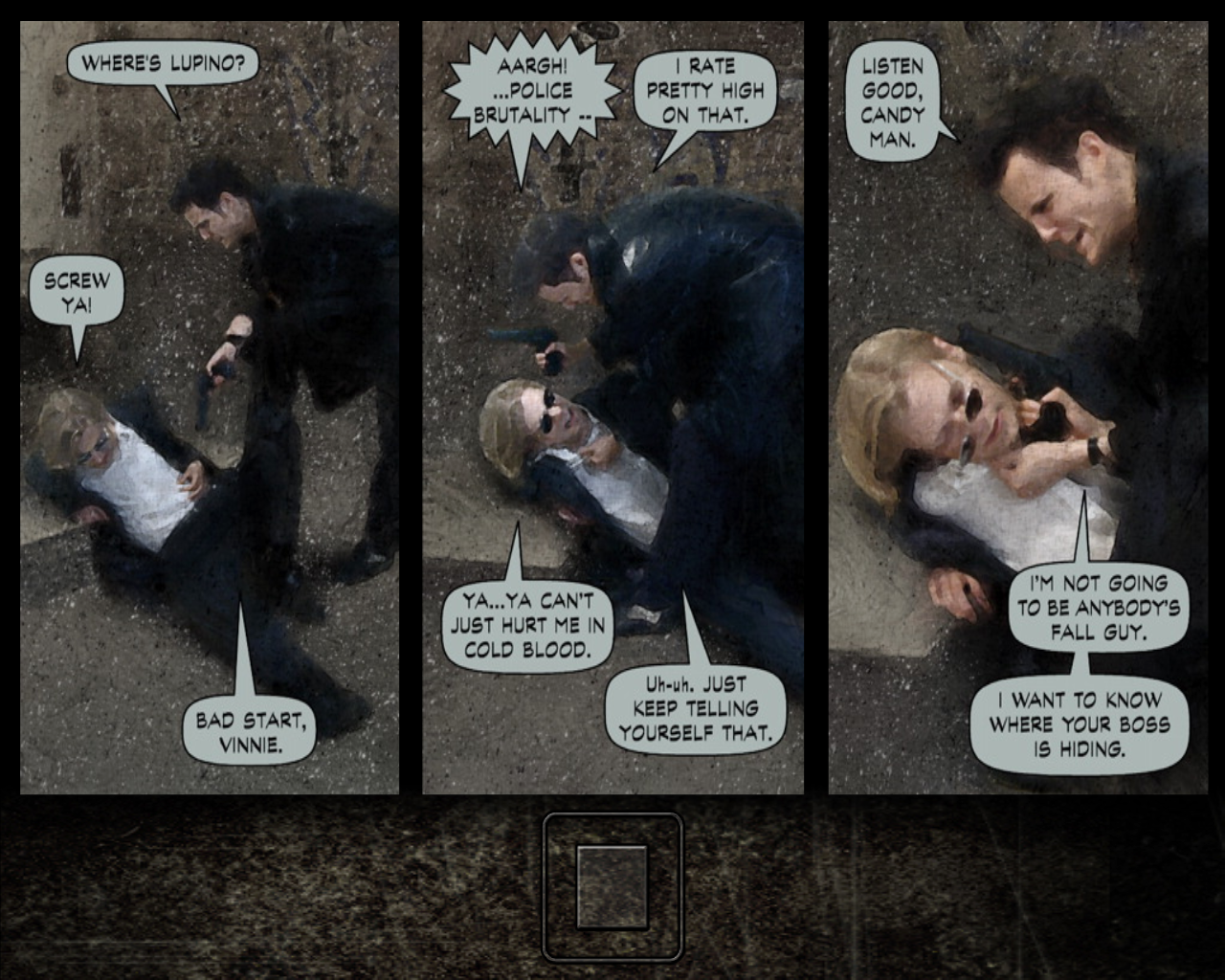

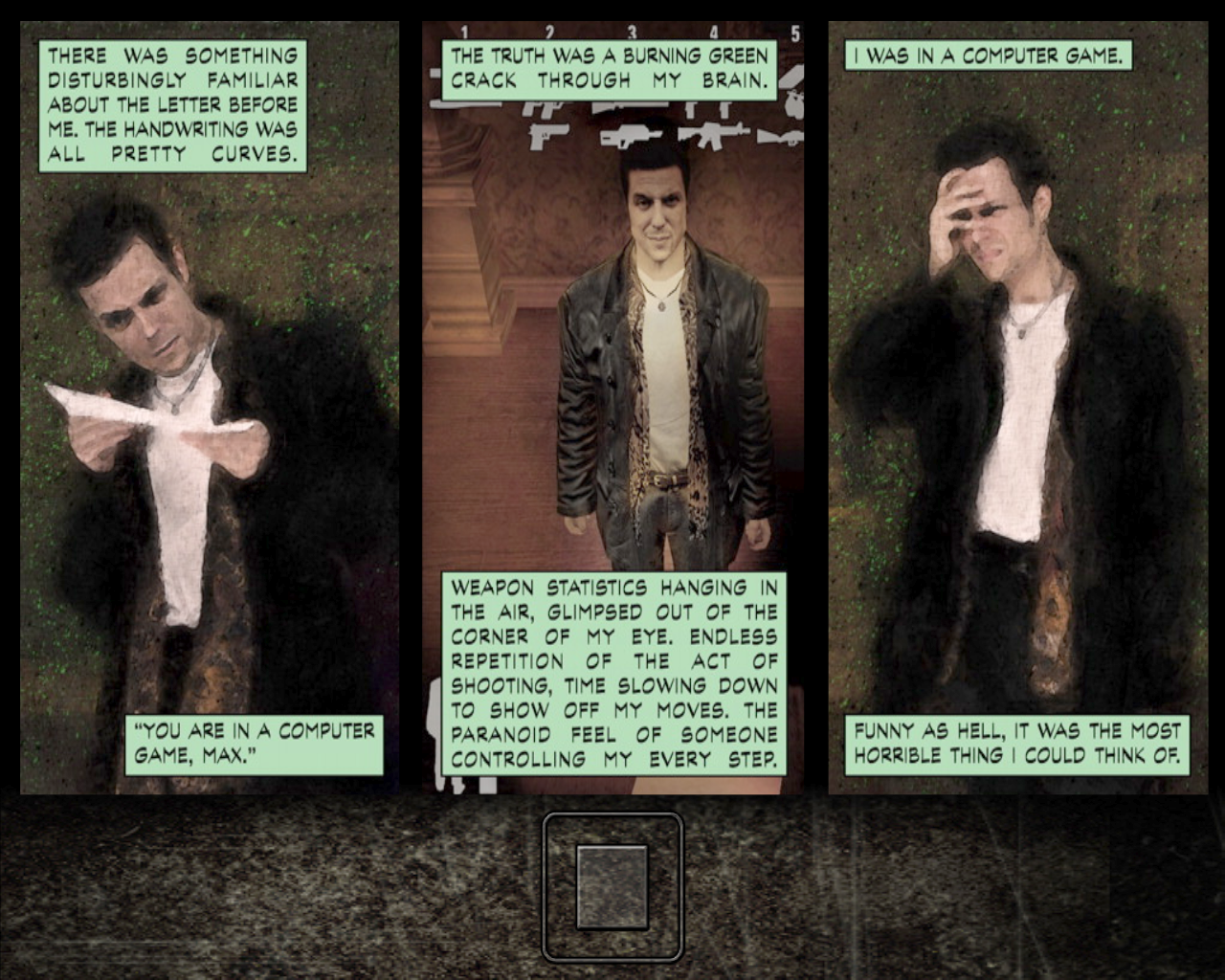

With a newfound focus, the format of the game changed rapidly. “We abandoned the top-down perspective and switched to 3rd person.” recalls Peter. “Also, the character and story started to get much better fleshed out once Sam Lake joined our ranks.” One of the many narrative devices brought in by writer Sam Lake was the inclusion of graphic-novel-style cutscenes. And although he focused the narrative into a powerful and troubled tale of vengeance, democracy was still present during story development. “Everyone contributed ideas.” Peter explains. “All the characters and stories evolved in a rather organic manner; some details were added, considered, then dropped, while other aspects stuck and grew. In some earlier versions of the story, the Valkyr drug mutated people into monstrosities. But that was abandoned.”

And whilst a memorable name and well told narrative were crucial for success, the gameplay was equally, if not more, so. Max Payne is widely remembered for one trademark mechanic: bullet time. Although it was not the first game to feature slow motion during gun combat, it moulded it into a smooth system which could be easily controlled by the player. “This was one of my key contributions to the game,” Scott proudly states. “I was visiting Remedy and they were showing me a very cool feature they’d added: slow motion enemy deaths. I was immediately struck with the idea that we needed to not just have this slow motion technology be cool eye candy, but that we needed to make it part of actual gameplay. My insistence on this idea got the Remedy team thinking about how to do it, and I suggested having a button the player could press that would shift the game into slow motion mode, with the exception that Max could still aim in real time.” But as Scott reveals, it was the main reason that multiplayer was left out. “The best we could come up with was that the bullet time effect was localised to within forty feet of the player, so that players outside this bubble remained in normal time. But it's extremely hard to make part of the game appear to go slow, while another part still goes at normal speed.”

However, the experience didn’t suffer, with bullet time being coincidentally enhanced by an earlier design decision: the rejection of the traditional hitscanning method seen in shooting games. “Hitscan is a technique that, in the most simple terms, means that when a gun is fired, an immediate invisible straight line is drawn from the gun to the first object it hits, whether an enemy, object, or wall,” Scott explains. “In effect, the bullet moves instantaneously through the environment, while real bullets travel between 700 to 1200 miles an hour. So, as a way to make Max Payne a more realistic game, an early idea I pitched to Remedy was to not use the hitscan method, but to model the bullets travelling at a realistic speed through the environment.”

Remedy took the bullet time mechanic even further by adding stylish dives the player could execute. “Initially, Max's shoot-dodge dive could be done in one direction only,” explains Peter. “Once you chose which way to dive, you couldn't change your aim much, as rotating the whole character sideways would have looked very odd. But then our texture artist Teemu Heinilehto wrote a ‘Wouldn't it be cool if…’ email to everyone, proposing that the player should be able to aim in any direction after diving, and surely this could be done by blending the animations. So we spent quite a bit of time and effort on this, and the result was a blend of eight dive animations. Dive in one direction, turn any way you want. We couldn't cover aiming up and down, but still, doing three-sixty-degree turning was already quite an improvement!”

However, due to limited resources, Peter and the rest of the team had to get creative to make it happen. “The character animations were sort of rotoscoped. We recorded some video footage with a DV camcorder in a gym, with our friend (a gun specialist and martial artist) performing some dives for us, plus the usual running cycles and some death bodyfalls. I then took that video tape, and used an abandoned video editing deck VCR to look through the motions frame by frame on a TV screen, and animating the characters by hand accordingly. First the key poses, then refining the details. You see, back then motion capture was rare, noisy and super expensive.” But it wasn’t the only source of inspiration for Peter. “I realised I didn't have to rely on our own footage, I could also watch some Hong Kong action movies and see how the stuntmen performed their deaths, so I manually animated some death animations based on those.”

And it wasn’t only character movement which was sourced from outside influences. To accurately capture the look of New York City, Remedy staff members travelled to the famous metropolis, using photographs to create textures for the in-game environments. “There were many trends in the game industry at the time, and ‘use photos for more realistic results’ was one of them,” states Peter. “It was simpler back then because we had no normal maps or bump maps; you didn't have to account for false lighting cues. The lighting and shading was baked into the colour/diffuse maps. Done. To get perfect results you'd have to abide to very strict rules in lighting when taking the photos, but back then the game industry was still quite homebrew, garage tech, hire-your-friends kind of pioneering.”

An article published during the game's development showing some of photos taken during this trip by Remedy in 1999 is still available in the legacy portion of the 3D Realms website. You can view that here.

With the lack of motion capture accompanied by a modest budget, the team had to pool every resource possible to create character models. As Peter reveals: “Because we decided to use photo textures, we needed faces to photograph. The Remedy staff were the closest people we could find. The people in the neighbouring companies in the same office complex and friends of the devteam were the second closest. Simple as that. I somehow avoided having my face in Max Payne, but my father ended up in the game as one of B.B.’s mobs in the parking garage scene.”

Even though there were many jobs to juggle, Peter looks back fondly on the experience. “I appreciated the diversity of tasks - every day was different, and if one task was blocked, I could switch into something completely different. It kept things fresh.” And in the end, everyone’s hard graft paid off. The combination of exhilarating action gameplay, slick cinematics and a narrative fuelled by rebellious desperation proved to be a winner, with Max Payne selling over four million copies. It’s handling of bullet time and gunplay hugely influenced the action genre, with echoes of its design still being seen today. “We all had high hopes,” recalls Peter. “But it was still quite a pleasant surprise to have it succeed so well. Also, it meant we could keep our jobs!”

This article is reproduced with kind permission from Retro Gamer issue 143, available at: http://www.greatdigitalmags.com/view/retrogamer/3660/retro-gamer-issue-143